Europeans should make no mistake: President Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariff announcement is not a within-the-rules trade conflict. It's a full-blown attempt both at rewriting the international economic order and coercing Europe and other trade partners into obedience.

As one of the world’s other two major trade blocs, the EU holds historic and international responsibility in stopping a complete unravelling of the world economy. At the same time, the EU must understand the logic of Trump’s coercive bargaining. In the first instance, the EU’s tightrope act requires holding off and preparing vigorous EU retaliation.

1. This is no ordinary trade war, it’s economic revisionism and full-blown coercion

As Edward Luce writes in his Ten weeks that shook the world, brutality is now the point. Europeans would do well not to misread the antebellum and Trump’s casus belli.

President Trump’s trade war, allegedly to reindustrialise his own country, is much more than that: it’s an all-out attack on the global trading system, perceived by Trump as harmful and defunct, and a structured, coercive drive against America’s trading partners. In this, the US 'Liberation Day'-tariffs are characterised both by profound delusion and the determination to leverage US power and control to the maximum.

With his April 2 Rose Garden announcement, a minimum levy of 10% will apply to nearly all US imports from 5 April. Trump also makes good on his threat to impose sweeping “reciprocal” tariffs to rebalance perceived trade restrictions by trade partners, such as tariffs, taxes and subsidies, as well as so-called currency manipulation. For Europe this means tariffs as high as 20% as of 9 April for Japan and China, 24% and 54%, respectively.

Since taking office, President Trump has already rolled out 25% tariffs on steel, aluminium, cars and automobile parts and threatened across-the-board 25% tariffs on all buyers of Venezuelan oil and gas. When the EU dared to push back against some of these, he threatened 200% retaliatory tariffs on EU wine and spirits.

Europeans who think this is a Mar-a-Lago protectionist monster to be tamed are not getting the message. The Americans will brook no indulgence, partnership or alliance with anyone. On the contrary, the message is 'Uncle Sam is coming for you'. On a par with previous targets Mexico and Canada, Europe is a prey to the US. For poorer, defenceless countries it will be even worse: if they’ve been hit in the first round by tariffs, it is because they will face extortion for natural resources or assets in the next.

The scale of this US Administration’s capacity for cynicism and revisionism should come as no surprise. After all, it is negotiating Ukraine’s partition with Putin’s Russia and trying to loot the victim in the process. It is drawing up new territorial designs in the Arctic and the Middle East, intentionally undercutting the international rules-based order as well as the fundamental interests and norms that constitute the West’s backbone.

Without doubt, Trump’s actions pose a serious challenge to Europe. As a bloc, the European Union is reliant on trade for a large chunk of its GDP, much of which is trade with the US. For trade in goods, the EU has a significant surplus with the Americans.

As matters stand, transatlantic relations are already deep into coercive territory and will remain there for the foreseeable future. The Executive Order 'Defending American Companies and Innovators From Overseas Extortion and Unfair Fines and Penalties' takes direct aim at and threatens retribution against actions by the Union in competition policy and digital regulation.

There have been repeated threats and intimidations that security and defence cooperation and NATO funding hang in the balance. The threat to the security umbrella is seemingly based on deep resentment and 'loathing of European free-loading' (imagined or real), as the accidentally published Signal exchanges between the US Vice President and Defence Secretary recently revealed.

Realities, in the first instance in the form of increased prices on US consumers and business, will carry weight in the US too. But even as costs go up, expect no automatic climb-down or return to normal. With the Rose Garden address came also in subtext the classic 'Madman-message': 'if the world falls apart, all will be worse off, but I slightly better'.

2. Fundamental EU objectives: Gearing up for coercive bargaining yet avoiding the protectionist death spiral

The EU holds a singular responsibility in this moment as one of the world’s three major trade blocs. It must balance the simultaneous pursuit of two critical objectives: taking leadership in salvaging the open economic order and up its game in coercive bargaining in defence of its own interests.

A look back to the 1930s is instructive as to how quickly world commerce and political structures can unravel when protectionism rears its ugly head. As illustrated by the Kindleberger spiral, over just four years between 1929 and 1933, world trade contracted month by month to less than a third of its original value.

Of course, the structure of the global economy today is not comparable to that of the 1930s, and trade barriers were not the sole, or even main, cause of the Great Depression and its aftermath. Yet it remains a powerful cautionary tale of unintended and unforeseeable consequences of unchecked protectionism and retaliatory spirals.

In a scenario of escalating tariff retaliation, Aston University economists point to a $1.4tn hit to the world economy, including widespread trade disruption, rising prices and falling living standards.

Going forward, Europe will be walking a tightrope trying to keep retaliatory and protectionist dynamics in check while responding to President Trump’s trade assault on Europe’s economy. In a context of coercive bargaining, where weakness becomes the pretext for further extortion, no retaliation is not an option. Retaliation must be well calibrated as an incentive, both in strength and in time, to bring the US to the table.

The EU did not want this; the offer to deescalate must always be there. At the same time, a negotiated outcome will always remain uncertain. As part of its response, the EU must therefore also prepare its citizens and businesses for the brutal reality that nobody ever wins a trade war and that everybody will suffer in this.

3. Lessons so far: European cooperative offers, and equivocation, have failed

In preparation for negotiations, the EU leadership must learn from past experiences and failures in defusing US trade aggression. Over the past months, high level officials in President von der Leyen’s immediate entourage have shuttled back and forth to Washington in attempts to better read the US Administration’s intentions and stave off the worst. If this objective ever was achievable, it has manifestly failed.

This is not the first time the EU locks horns with the US. Already in 2018, Trump doled out tariffs on steel and aluminium, amounting to 25% on the former and 10% on the latter. In response, the EU hit the US with tariffs targeting €2.8 billion worth of American goods, like Harley Davidson motorcycles and Levi’s jeans. Additionally, the EU acted under the WTO Safeguard agreement raising tariffs on steel products against other trade partners to alleviate the damage to domestic industry.

Finally, the EU’s then Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker struck a deal with President Trump during the summer in 2018, promising to increase imports of US products to reduce the EU trade surplus in goods. Famously, the political deal pledged a largely hypothetical increase in soybean imports from the US to the EU.

The instructive element is that none of these measures were able to persuade Trump to remove the steel and aluminium tariffs on the EU. They may have stemmed further trade restrictions but a deal on the existing ones wasn’t struck before 2021 with President Biden in the White House.

Drawing lessons from past attempts at engagement is not easy, as there is no counterfactual. What seems clear is that President von der Leyen’s absence of leadership on tech enforcement, including signals suggesting readiness to back down on critical cases, has yielded absolutely nothing. On the contrary, if anything, it will have weakened both Europe’s defence against existential democratic threats and the EU’s negotiation stance.

President von der Leyen has talked boldly about building positions of 'strength to negotiate' but has in this instance done the opposite. The 2018 saga should have taught the EU executive that deals are possible, but they will have to face fire with fire when it comes to Trump. Prevarications or minor tariffs just won’t faze him.

4. Europe’s opportunity: Proactivity in defence of fundamentals and use of strengths

The first imperative in the coming fight is the EU27 sticking together in the face of the US onslaught. As retaliatory action is planned, the US will attempt to splinter off member states by direct contacts and tailored tariff exemptions on product categories dear to individual countries. Yet the randomness, scale and brutality of the US offensive can also have the opposite effect of rallying member states around the common commercial flag.

For that, it is essential that the Commission and its President, despite her instinct for presidentialism, deploy their capacities of shared leadership at technical and political levels to bring member states on board in a common strategy, including getting tough on member states, big or small, not inclined to toe a common line.

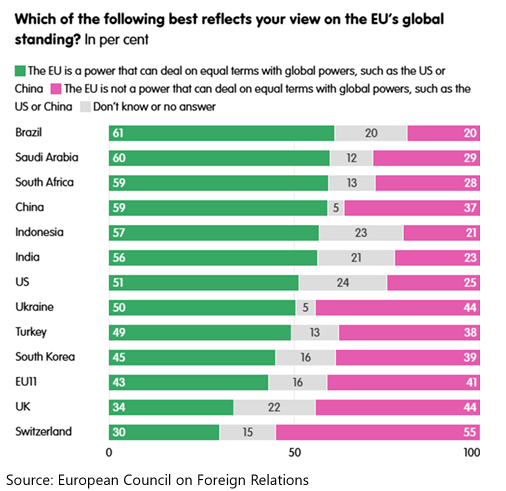

Collectively, Europeans need to straighten up and believe in themselves and the EU’s capacity to face these new and harsh realities together. As a recent poll by the European Council on Foreign Relations revealed, the only ones in the world who don’t view the EU as a power capable of shaping the world alongside the US and China are Europeans themselves.

Second, Europeans must shape their own narrative, negotiation path and economic future. A good start is rejecting that of President Trump. His worldview and story are built around the notion that the US is getting an unfair deal or being 'looted, pillaged, raped and plundered' as he put it, in the trade of goods. This despite EU tariffs averaging just 2.7 percent on a trade-weighted basis.

He also conveniently omits to factor in the US advantage in services, based on largely unfettered access to EU services and procurement markets. In 2023, the EU had a surplus in goods with the US of €155,5 billion and a deficit in services of €104 billion. This deficit in services has grown from €13 billion in 2018 and €20 billion in 2020 to triple digits in 2023.

If there ever was an imbalance and complaint to be levelled, it is probably this one: US tech companies and platforms have benefitted massively from open access to the European market, the world’s largest digital service market outside the US, with some inflicting significant damage on Europe’s economy, institutions and societal fabric through anticompetitive and antidemocratic practices.

According to the US Chamber of Commerce, in 2021, the U.S. exported $283 billion in digitally deliverable services to Europe, almost twice the amount going the other direction, and more than double U.S. exports to the entire Asia-Pacific region.

Brad Setser and Michael Weilandt have looked at the Income Balance Puzzle from the US perspective and concluded that the imbalances at play are almost entirely attributable to profit-shifting by US multinationals. The flip side of that coin, seen from Europe, has historically been called Ireland (in 2023, intellectual property represented 37.9% of EU27 services imports from the US, with charges for use of intellectual property having grown from a deficit of €5.4 billion in 2018 to €125.1 billion in 2023. Leagues ahead of number two, Germany, Ireland has become Europe’s number one importer of services, with charges for the use of intellectual property in its US trade accounts growing from €2.5 billion in 2018 to a full €110.9 billion in 2023).

International profit shifting and corporate tax evasion are the kind of imbalances that should truly be addressed – internationally, across the Atlantic and at home. Despite the OECD agreement struck in 2021, the US is still not applying the Global Anti-Base Erosion Rules (the so-called ‘Pillar Two’).

Now, President Trump’s announced tax policies, such as overhauling the US corporate tax code, withdrawal from the OECD tax convention and retaliating against 'unfair' foreign digital services and VAT – promise to wreck further damage. 'Tax where the value is created' has been a cornerstone of tax policies. For contemporary economies, and Europe, having effective frameworks to tax the value when it is in the cloud is a must.

President Trump will not negotiate with facts and people that don’t fit his narrative. But this only underscores the third major lesson and point: Europe must get on the front foot and do what is right for itself, whether through taxation and digital regulation, or by getting rid of dangerous dependencies by investing in technologies and defence of its own.

The EU also must double down on its core strengths – first and foremost the single market. As Mario Draghi recently pointed out, existing and new barriers to trade among member states impose a 45% tariff on intra-EU trade in goods and a 110% barrier on trade in services. Unlocking the potential of the single market is necessary to further reduce the US's ability to hurt us.

5. How we fight back: One date, one strike

Europeans are not bereft of trade defence tools and the economic foundations to face US trade aggression. But strength requires readiness to strike with firm countermeasures. The uncowed response by Mexico and Canada to Trump’s trade threats—and their comparatively benign treatment in the latest round—shows that the Americans will rethink when faced with steely opposition. That said, returning fire will be costly and fraught with uncertainty for Europe, and results will not be immediately visible.

a. The aim of retaliation is to reach a negotiated, reciprocal settlement, opening transatlantic trade rather than shutting it down. The EU should therefore avoid a knee-jerk reaction in the coming days. Instead, retaliation must be well-calibrated as an incentive—both in strength and timing—to bring the US to the table, including by targeting where tariffs will hurt President Trump’s political and electoral interests the most.

b. A clear schedule should be set out, giving the US time while also indicating when and how retaliation will strike, along with a draft term sheet for a reciprocal economic deal. The Commission has already indicated it would respond in one blow to Trump’s reciprocal tariffs and auto tariffs—which makes sense.

c. The retaliatory threat must be vigorous. Trump’s reciprocal tariffs are clear-cut and breach fundamental rules of international trade law, such as the most-favoured-nation principle and agreed tariff schedules. The EU can therefore combine different trade instruments:

i- WTO rules and Regulation (EU) No 654/2014 give broad leeway across different sectors to respond to economic damage through rebalancing measures. In response to US steel and aluminium tariffs, the EU has already promised countermeasures on US goods worth €26 billion, with a final list to be drawn up shortly.

ii- In light of the 2018 trade war, the use of coercive US secondary sanctions on EU businesses, and coercive actions by China, the EU added a further tool: the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI)—the EU’s much-vaunted ‘bazooka’. The instrument defines economic coercion broadly and covers 'legislation or other formal or informal action or inaction'. It provides the EU with a flexible set of retaliatory options listed in Annex 1, covering, inter alia, tariffs; restrictions on goods imports, services, public procurement, investment, and intellectual property.

The procedure for triggering action under the ACI is not quick, but if there is political will, retaliation could be highly effective if smartly calibrated.

The breadth and flexibility of the ACI allows the EU to approach retaliation creatively. In addition to forceful action on services, one out-of-the-box idea could be to require that IPR charges suspected of profit shifting be placed into an escrow account—until adequate tax frameworks and agreements are in place, in line with international obligations.

iii- Last, WTO rules and Regulation (EU) No 654/2014 also allow for safeguard measures—trade barriers that can be drawn up towards allies and rivals alike—to protect domestic industries from import shocks. The EU did this with the steel safeguard in 2018, now extended until 2026. Increasing trade barriers with allies is a sensitive issue. The Commission will need to carefully assess whether market conditions are severe enough to justify such measures, which can lead to retaliatory spirals. Yet, these measures seem inevitable for goods where Chinese overcapacity and trade diversion—amplified by the US-China standoff—now pose significant risks to European industry.

d. In parallel to direct retaliation, the Commission must reinforce its defence of fundamental principles and interests. Faced with both direct pressure and the reflexive influence of the US Administration and Big Tech, the second von der Leyen Commission has thus far shown too much deference and hesitation in enforcing its digital rulebook, such as the Digital Services Act. The temptation to offer rules and regulations as bargaining chips in a broader deal with the US must be resisted at all costs.

The EU must uphold legal certainty and its democratically adopted laws, and maintain its credibility as a predictable rule-setter—including, where possible, in international fora such as the WTO. Ironically, current US trade aggression could serve to reinvigorate talks on multilateral reform and stimulate ideas for a possible 'WTO 2.0'.

e. None of this excludes the possibility of a positive-sum settlement with the US. Brussels has begun preparing a package of trade options for the Trump Administration. This is likely to include an offer to purchase more American natural gas, as global energy flows adjust to US punitive measures. It has also signalled a willingness to lower auto tariffs to match the US level.

More significantly, in exchange for a US climbdown, there may be scope for a series of economic security deals. The list of exemptions from the latest tariff round—covering goods like semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and certain minerals—suggests a recognition in Washington of the need for nuance and differentiation.

In core sectors such as steel and aluminium, critical raw materials, semiconductors, healthcare, and clean tech, EU–US economic security agreements could combine joint responses to Chinese overcapacity and strategic dependencies with commitments to keep the transatlantic space open, based on bound/applied tariffs and reciprocal access to subsidies and procurement.

Ultimately, the EU has its own interest in acting more forcefully to diversify and secure supply chains. This may require a mix of tariff tools, regulatory action, and security measures—particularly with regard to China.

Finally, it is important to recognise that the EU is not alone in facing Trump. As the US president targets allies and enemies alike, the EU should strive to strike deals, partnerships and alliances with other countries targeted by Trump and seeking to derisk their relationship with an increasingly unpredictable US.

After legislating the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930, one of the most significant responses to the US protectionist push was Canada turning towards the UK for trade. This greatly damaged the US economy. The EU should seek to close ranks with the US’s northern neighbour once again, and must similarly keep diversifying its trade with other partners, as it has with the recent Mercosur deal.

The EU’s attractiveness, not only as the biggest market in the world but as a reliable and predictable partner, is growing by the day and creates new opportunities. At the same time, Europe has also to get ready for sharp reversals in global trade, a protracted period of uncertainty, and the risk of a prolonged unfriendly trade environment. History teaches that tariffs unfortunately tend to be sticky. As seen in the 1930s, it took years to start inching the spiked tariff levels down to previous levels and to unlock the regionalisation spawned in response to the Smoot-Hawley tariffs and the Great Depression.

Into the unknown

Henceforth, the waters are uncharted. President Trump has unleashed the kind of forces that lead to colossal, brutal, upending changes imposing huge costs on everybody. We are in presence of dynamics that no political prediction or econometric model can truly capture, but that historically have led to major wars and upheavals, the passing and birth of hegemonies and the redrawing of the world order.

EUropeans must be ready to meet the unknown and face, and shape, this future together.